Author bio: Emily Price is a freelance writer and a PhD Candidate in medieval literature.

If you lived in the Middle Ages, you’d probably be a laborer. Videogames don’t usually represent this statistical likelihood, and strategy games like Crusader Kings and Age of Empires make you a king or a general above the people. Manor Lords is no different: you pick a sovereign at the beginning and a herald to go along with them. But it’s much more focused on the particulars of agricultural labor than I expected, and more interested than other games of its kind in simulating the workers who perform it.

“Labor alone, not leisure, recreation, singing, wooing, nor idyllic landscapes… is the defining characteristic of rural life in the Middle Ages,” argues scholar Katherine Little. Agricultural workers were the vast majority of the population, and were the subject of pastoral fascination well into the Renaissance. Manor Lords places you in charge of a medieval village to defend and nurture, and it also puts you in charge of a lot of those workers. I spent most of my time in the peaceful mode (“Rise to Prosperity”) where I didn’t have to deal with combat. Mirroring the medieval peasant, I focused on building farms, for which I had to build granaries, which I had to staff with more workers.

The first thing you might notice about Manor Lords is how large a scale it’s trying to represent, in terms of size—you start on a huge map that you can zoom out until your tents are a dot among waving trees—but also in terms of effort. In the ancient world, it took a lot of labor to produce food. Large families tilled small farms of about three to five acres. A medieval manorial farm (which covered about a third of farmable land) could be staffed by many different families whose various members worked the fields at different times depending on what was needed (planting, sowing, harvesting, etc).

While those with peasant plots merely paid taxes on the land, dependent laborers experienced, as David Levine puts it, “a ‘double rent,’ on both the land and their bodies”. The labor shortage brought on by the Black Death in Europe—and shortly after, the Peasants’ Revolt—led to disruptions and food shortages that emphasize how key agricultural work was, and how many workers it took to create a steady food supply.

Manor Lords understands the amount of manpower that food production took, and it makes that effort more obvious by slowing it down. Buildings like farms and markets must be very large to be effective, and they need efficient roads to connect them. Citizens actually walk pretty fast, but when you’re zoomed out they crawl along like ants from the storehouse to the clay pit and back. Putting related buildings together and connecting them with roads is vital to getting anything done.

My biggest problem was getting enough families to move in and staff all the workplaces and stalls, which were crucial to running trade. Each family in Manor Lords has one workplace, and it takes a while to build up enough families to support more than a very small town. This cycle accurately represents the amount of effort it took to produce enough food to keep a family, village or manor running. It also makes those who do that work, and their habits, front and center.

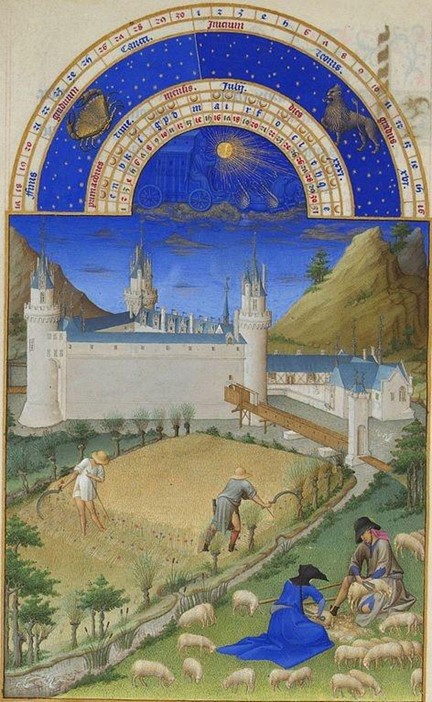

Those habits change depending on the weather and the season, as well as the presence of disease. The seasonal cycle is important to the game, as it was in medieval peasant households. Harvest time, which comes in September, reminded me of the Labors of the Months, a famous series of medieval illustrations made for Jean Duc De Berry in which peasants stoop to thresh grain in July and huddle around a fire in February. Like medieval farmers, whose workloads increased at harvest time and dwindled afterwards, villagers in Manor Lords don’t do very much in the winter. They’re vulnerable to nature’s changes, whether getting sick in a sleet storm or having livestock run away.

Speaking of livestock, they all have a name—medieval people did name their pets, by the way—as does each villager. Workers will talk to the other people at their worksites or in their houses, and if you zoom in you can eavesdrop on them. On one hand, hearing peasants say “summer is coming soon” as you scroll over them makes you feel more like you’re observing a changeable world.

At the same time, these conversations reminded me of the fictionality underneath the medieval strategy game as a concept. After all, any modern representation of the medieval world is a simulacrum. Deciding how to represent the medieval past relatably, in a way an average person understands as “medieval”, involves erasing language, mannerisms, and conversation topics with your own imaginings. In this case, that’s a lot of chatting about one’s workplace, while suffering from generic cockney accent #1001.

This is the biggest thing I’d like to see improve as the game develops further in early access: more voiced lines for your subjects, with more variety about things they experienced in their lives besides work. I’m sure there’s drama going on under the surface of my town, and I want to hear Frederick and Nickel complain about their tax rates and gossip about their lazy neighbors while they chop down trees.

Dialogue aside, Manor Lords emphasizes its peasants as full people through their daily rhythms of going to the tavern and lingering in the fields to talk to friends. You get so used to watching them hang out that it’s jarring to remember you aren’t playing as one of them.

While Manor Lords lets you order your subjects around, it’s much more about them than it is about you.

A year into my first playthrough, I clicked the game’s equivalent of Google Street View, which lets your monarch walk around your village and observe it from peasant height. My monarch kept walking into fence posts—this feature is still early in development—and their luxurious bright red outfit stuck out like a sore thumb against the flower-dotted grasses lining the road. The village was full of natural beauty, and I was the scythe meant to slash it into order. I clicked out of the view before I walked into the woods, relieved to see things from above once again.

While Manor Lords lets you order your subjects around, it’s much more about them than it is about you. Its accurate representation of medieval agricultural systems is an achievement, but what I found more impressive was that it represents medieval peasants and their lives more fully than most games—and honestly, most media properties—I can think of. While that’s not an especially high bar, it is an encouraging sign of a desire to depict the medieval past, a time of cultural diversity and technological innovation despite its reputation as a “dark age”, more complexly. We might be waiting a while for the strategy game where you play as a peasant—a farming sim, probably—but until that comes, Manor Lords is the closest you can get.